|

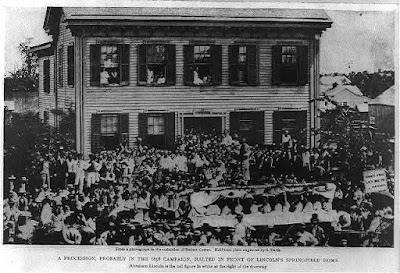

| Image from the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library & Museum. |

Now that time was nearing an end, as Abraham Lincoln,

President-elect of the United States, prepared to leave Springfield for the

journey to Washington. Outside the Great Western Railroad station at 10th

and Monroe a crowd had begun to gather to wish him farewell on the chilly,

dreary morning of Monday, February 11, 1861.

They were friends, neighbors, community leaders,

well-wishers and strangers who simply wished to be part of the momentous event

about to occur. Even when the skies opened and a cold rain began to fall they

gathered around, eager to catch a glimpse of the man in whom they had entrusted

their hopes for peace and the survival of the nation.

The Lincoln family had spent their last few days in

Springfield winding up their local affairs. Lincoln had placed an advertisement

in a newspaper and offered for sale many of his house’s furnishings. Even the

family dog, Fido, had been sent to live with a family in the Lincolns’

neighborhood.

The day before, Lincoln had met with his law partner William

Herndon to wrap up any outstanding cases and paperwork at his law office at 6th

and Adams. Upon leaving the office Lincoln had noted the “Lincoln &

Herndon” sign hanging above the office door. “Let it hang there undisturbed,”

he said to Herndon, “Give our clients to understand that the election of a

President makes no change in the firm of Lincoln and Herndon. If I live I’m

coming back some time, and then we’ll go right on practicing law as if nothing

had ever happened.”

“If I live,” he had said.

A few minutes before 8 a.m. Lincoln emerged, along with his

neighbor Jameson

Jenkins, and several trunks with hand-labeled cards attached: “A. Lincoln,

White House, Washington, D.C.” A muted cheer went up from some onlookers who

had decided not to wait with the crowd at the station. As they shivered in the

rain Lincoln acknowledged them with a wave. He and Jenkins then loaded the

family’s luggage into the wagon and a separate cart waiting for them at the

bottom of the steps.

As the carriage departed for the short trip to the Great

Western Depot, the crowd fell into formation behind it. For the rest of

their lives its members would be able to tell their descendants that they

escorted Abraham Lincoln to the train station when he left for the White House.

|

| Lincoln at home in Springfield, standing inside the fence with his son Willie. |

Shortly after Lincoln’s election in November, southern

secessionists had met to take the long-threatened step of disunion. Fearful

that the election of a northern Republican; who had won the White House with no

southern votes; would lead to the abolition of slavery, southern leaders had

assembled in secession conventions in their state capitals to debate

resolutions dissolving the union which bound the country’s 34 states together.

South Carolina had gone first on December 20. Once that line

had been crossed, six other states followed like a row of falling dominoes:

Mississippi on January 9, 1861, Florida the next day and Alabama the day after

that. Georgia had followed a week later, then Louisiana and finally Texas.

Seven more slaveholding states, Tennessee, Virginia, Maryland, Arkansas, North

Carolina, Missouri and Kentucky took a wait-and-see approach. It seemed that

the only piece of good news had come in early January when Delaware voted down

a secession resolution. The weekend before he left Springfield Lincoln had

expressed to his Springfield friend Orville Browning no confidence in an

ongoing Peace Convention being held in Washington to find some kind of

compromise to stave off disunion.

The outgoing president, James Buchanan, did little to prevent

the breakup of the Union, writing in his State

of the Union message in December 1860 that while he thought secession and

disunion was a bad idea, there was nothing he could do to stop it. Buchanan;

whom historians have consistently ranked as the worst President

in American history; also took a moment to criticize the north’s

“intemperate interference” with slavery.

Buchanan’s administration had dispatched an unarmed

steamship, Star of the West, to bring

supplies to U.S. Army soldiers garrisoning a little-known South Carolina island

outpost called Fort Sumter. When the ship was fired upon it withdrew back to

New York. The now-stranded Army troops in Fort Sumter were led by Major Robert

Anderson, who had been Lincoln’s commanding officer during his time in the

Illinois militia 30 years earlier.

All this weighed heavily on Lincoln’s shoulders as the

carriage jostled over the streets toward the train depot. The group of spectators

now joined with the even larger crowd assembled outside the station where

Lincoln and some local dignitaries would board the special train. By some

accounts the size of the crowd that morning had swelled into the thousands.

Lincoln’s departure was a bittersweet moment for the people

of Springfield who gathered in the increasingly heavy rain. Most of them had

known Lincoln personally, some for many years. The young lawyer had moved to

the soon-to-be capital city in 1837. He had easily made friends thanks to

his casual manner and legendary storytelling. The crowd consisted of former

clients and fellow lawyers, friends from his time in the legislature,

shopkeepers and merchants who had greeted him on the way to his office, and

others from every walk of life to be found in Springfield.

His entourage this morning included his son Robert,

secretaries John

Nicolay and John Hay and his bodyguard Ward Lamon, plus an assortment of

Illinois politicians led by Governor Richard Yates, lawyers, railroad officials

and even Lincoln’s Springfield banker. Writers from many of the big eastern

newspapers were also along, many of them already seated on the train as Lincoln

had told them the day before that he would say “nothing warranting their

attention,” before leaving Springfield.

But now, boarding the train’s rear platform and looking upon

the enormous and adoring crowd which had come to see him off, an emotional

Lincoln decided to offer a few words. The crowd hushed as he removed his famous

hat, many of the spectators doing the same despite the weather. There was no

prepared text for his extemporaneous remarks, he spoke straight from the heart.

It was only afterwards that reporters asked him about the speech which he and John

Nicolay did their best to re-construct,

with accounts differing slightly as to his exact words. But the spirit of his

remarks, the gratitude he expressed, the deep concern for the challenges he

faced and his sincere request for help from above come through as clear as day.

The crowd pressed forward to hear as Lincoln stepped to the

railing to address them for what would turn out to be the final time.

“My friends - No one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feeling of sadness at this parting. To this place, and the kindness of these people, I owe everything. Here I have lived a quarter of a century, and have passed from a young to an old man. Here my children have been born, and one is buried.

“I now leave, not

knowing when, or whether ever, I may return, with a task before me greater than

that which rested upon Washington. Without the assistance of that Divine Being,

whoever attended him, I cannot succeed. With that assistance, I cannot fail.

Trusting in Him, who can go with me, and remain with you and be everywhere for

good, let us confidently hope that all will yet be well.

“To His care

commending you, as I hope in your prayers you will commend me, I bid you an

affectionate farewell.”

Abraham Lincoln then turned and boarded the train, departing for the nation’s capital to save the Union and become the greatest President in American history.